|

"They're terrified". This was one of my first realizations about my high school Art 1 classes. When I presented an interesting assignment with lots of choice, many shut down. They asked me to just tell them what to. They wanted steps to check off when I'd planned an adventure. This, of course, makes sense. Our educational system doesn't teach children to question or imagine, it teaches them to be compliant. So, by the time kids get to high school many have lost their love of learning. They don't remember how to play and explore. Bootcamps, which I only do with Art 1, follow this format: - Teach a concrete skill quickly by asking kids to apply new knowledge as they use it to accomplish close-ended tasks in groups. - Use the newly learned skill as a jumping off point to teach kids a framework for creative decision making (I use a format called Design Process Thinking) by asking them to apply what they've learned in an independent, open-ended task. Example: learn a bit about how a range of drawing materials work, then pick one, plan and complete your own drawing. Bootcamps are the bridge between compliance and independent thinking.

Bootcamps level the playing field by teaching general information about a range of media. During Bootcamps, kids re-learn how to explore and play, to enjoy the adventure that learning should be. After a few weeks, I can introduce a unit like "Artist Take a Stand" and my Art 1 kids can tackle it with excitement and confidence. No terror.

1 Comment

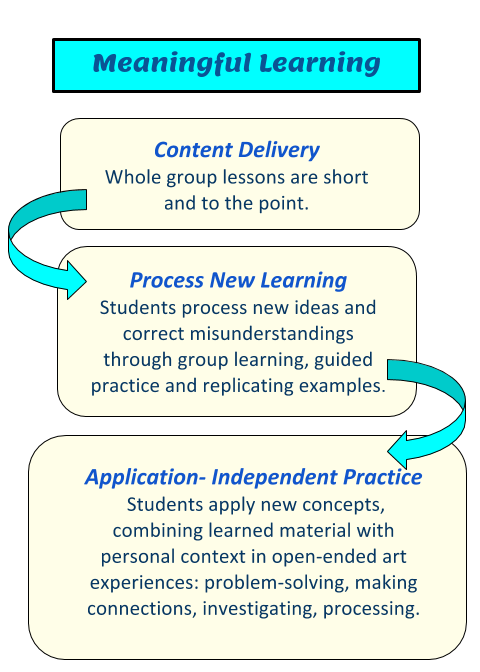

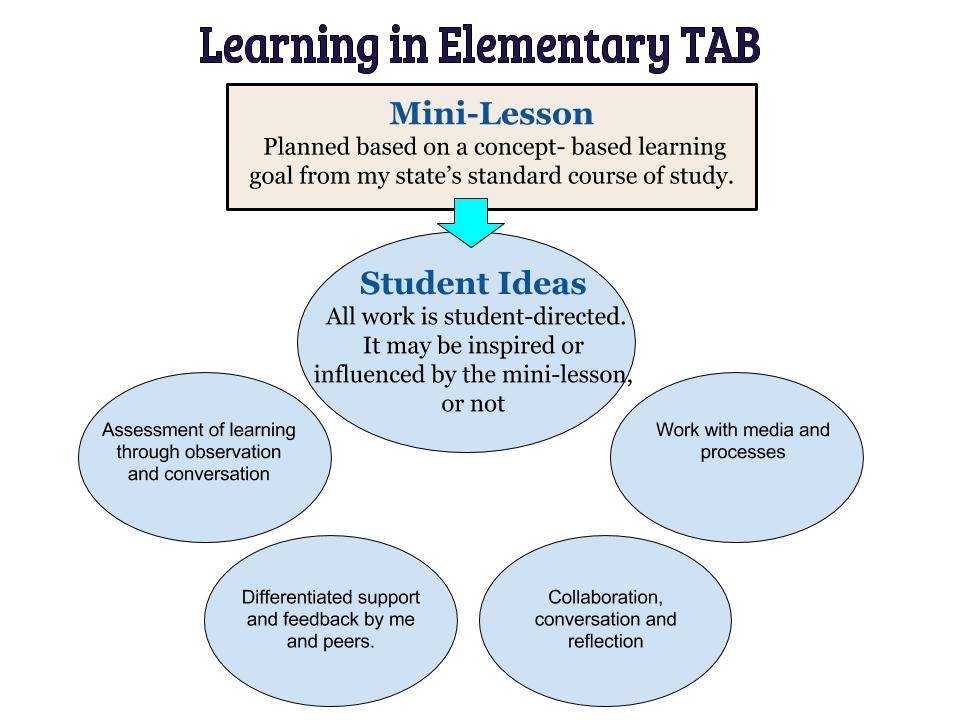

"Why can't my kids mix colors?" I remember thinking in my first few years of teaching. I had taught my kindergartners how to mix secondary colors just a month ago, and now it seemed like half my class had forgotten. It couldn't have been my lesson - their paintings inspired from the book Mouse Paint, complete with little cut paper mice, almost all had correctly mixed secondary colors. It was my lesson. I had taught the color theory and I had provided guided practice but I had stopped short of doing what needed to happen for my kids to really learn the material. I hadn't given them a chance to apply new learning. When I switched my elementary classroom over to TAB I worried that skills like color theory might be harder to teach. I was surprised to find that the opposite was true; students learned and retained information much better. The reason? I was now giving kids ample time to apply new learning as they worked in centers. Kindergartners, who in years past had been unable to remember how to mix orange, easily mixed all the colors they needed from primaries in the Painting Center. I'd demo, let them practice together, then provide the opportunity to apply new learning every time they needed to mix colors. This same formula works at high school, whether it's applying technique to draw, thinking about color theory to mix paint or using understanding of perspective to draw an anamorphic illusion. The key to getting students to remember new learning is giving them the chance to apply content as they investigate their own ideas. This requires them to process and store information as they use it to accomplish their goals. This can't happen if your lesson doesn't go farther than kids replicating your example. We have to make learning meaningful by expecting students to apply concepts as they work to accomplish their own artistic goals.

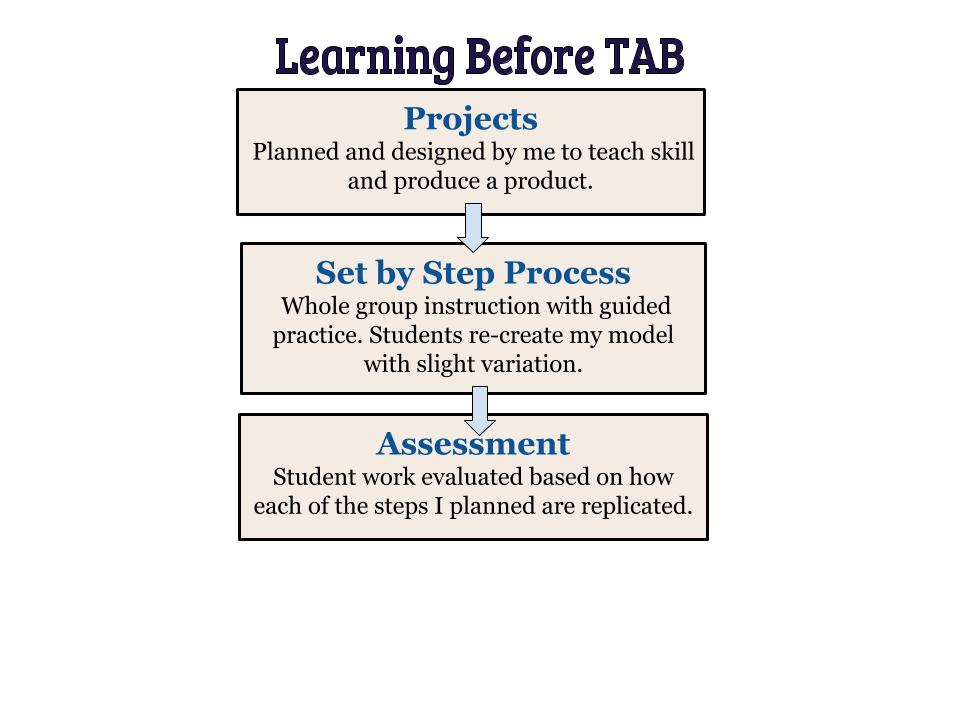

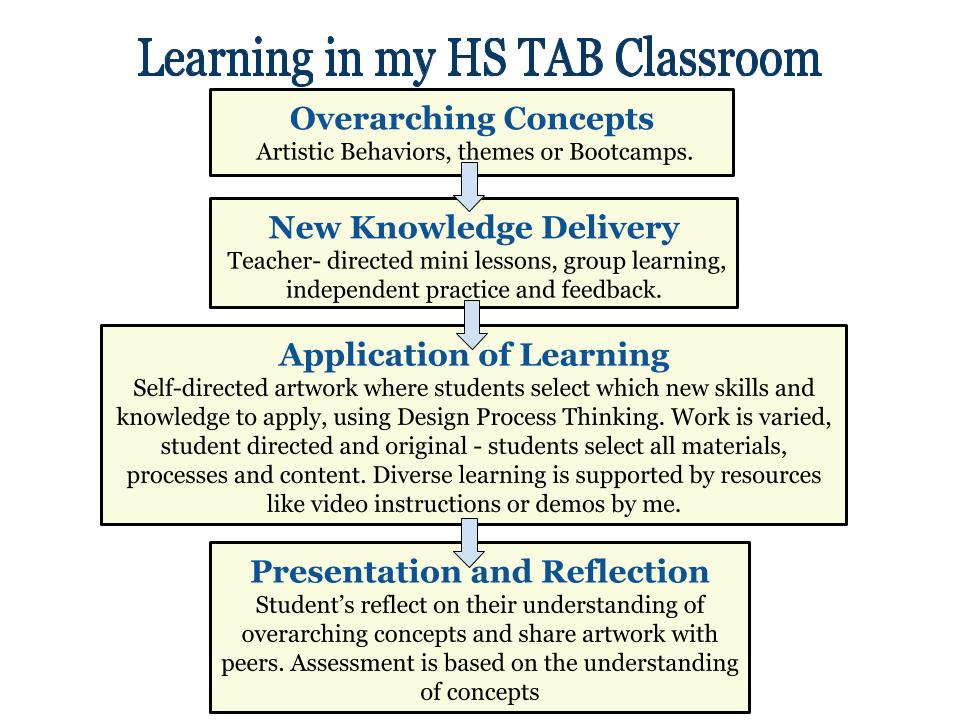

Explaining the deep learning that comes from a TAB classroom to a teacher who hasn't tried it is hard. In fact, the first time I heard about TAB I thought it sounded impossible. My class was very teacher directed and looked like the diagram below. Over time, my teaching style became more and more open. I kept coming back to the idea of TAB because I saw how increased levels of autonomy lit a creative fire in my students, especially the ones that were the hardest to reach. Learninging in my TAB classroom looked very different from my previous teaching. One of the biggest differences was that the learning structure wasn't linear - it was a continuous cycle of engagement. Another was that a very organic sort of collaboration between students happened regularly. Since everyone was doing different things, kids were very interested in each other's work. Peer mentoring, working together on big ideas and conversation about artistic choices were the norm. Since I was no longer spending my time planning projects and walking kids through the steps, I spent my time differentiating support on a individual basis and talking to students about their work. This structure changed when I moved from elementary to high school. One key difference was that students were much less confident in their ideas and needed more support in generating and developing them. The structure of my teaching changed to provide that and I developed Design Process Thinking as a scaffold for teaching creative thinking. When comparing a TAB structure to one with less student choice there is a key difference is the application of ideas. It was missing in my pre-TAB classroom. When the teacher plans the project and teaches it in steps, the students only copy a model. This sort of replication creates little lasting learning because information doesn't have to be remembered, processed or applied in other contexts. However, when students are asked to come up with their own ideas or select from a range of options, without the crunch that the teacher model presents, we really get to see what kids can do.

The sort of teaching I was doing pre-TAB has a place in art ed - as a skill-teaching precursor to an experience where student can apply knowledge. To see what our students really know and can do we can't list the steps for them. To develop student's creativity and voice we can't plan what they are going to say - instead, we have to give them space to say it. How do you know when your instruction has been successful? In my Art 1 classes, the time for reckoning is always at the first Artistic Behavior Unit. Prior to that, I'm laying the foundation by introducing media and technique in Bootcamps. Just as importantly (and maybe more so) I'm scaffolding independence by teaching kids how to use Design Process Thinking to plan and make their own work. I wonder, after weeks of Bootcamps, are they ready to pick media and develop ideas? I start slow. Our first unit is Artists Understand Space. We begin with a series of mini-lessons, used to examine the the element of Space - which I define as "how an artist uses or manipulates length, width and height, or our perception of them" - from multiple perspectives. We spend a day with forced perspective, playing with compressing space. Next, we spend a day on one point perspective creating realistic space. Kids work in groups to draw the hallway, which helps them understand the process in a short time. On day 3 we make geometric tape murals. (lesson plan here) Next comes the part I hold my breath for. Mini lessons are done and it's time for students to investigate Space in a work of their choice. I review what we've covered in mini-lessons and show a few examples of artists that use Space in their work. "Okay", I say, referencing my Design Process Thinking model. "There is your Inspiration. Now Design in the way that works best for your needs." I do attendance, then look up 10 minutes later and see kids experimenting with anamorphic drawings, planning to use forced perspective in stop motion films and brainstorming where in the school might be best for an architectural drawing.

All on their own. That's when I know my instruction has been successful. |

Mrs. PurteeI'm interested in creating a student student centered space for my high school students through choice and abundant opportunity for self expression. I'm also a writer for SchoolArts co-author of The Open Art Room. Archives

December 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed