|

I firmly believe that to be a good teacher you have to constantly question your practice. Over the last year, I've been questioning how my teaching supports equity - which I see as creating equal opportunity for all students in the classroom. For me - and, just to be clear, I'm only going to address my personal experience here - to understand how to support equity in my classroom I have to examine what makes it unequal. A big part of that is the legacy of colonization on both visual art and on schools.

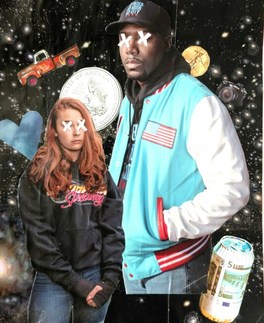

What I learned in that class was impactful and important, but so much that I needed to know as a teacher was missing. As a new teacher I felt pressure to teach about the important artists I'd learned about and there didn't seem like there was room for much else. I also included art from non-western cultures in my teaching, but I did not have the understanding or breath of knowledge to do it well. Additionally, the art we did learn about was an incomplete story. We talked about Greek art, for example, but not about how so much of it ended up in the British Museum when Lord Elgin literally sawed freizes off the Parthenon while Greece was under occupation. We learned about great white, male artists - but not about the societal barriers that kept women from participating in the arts. We certainly didn't learn about the women who, against all odds, were there. Years later, things are changing. Places like Greece, Nigeria and Rapa Nui (Easter Island) have been asking for art that was taken under colonial rule to be given back for decades. In the last month, first the French government, then the British have agreed to give back the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria. These works of art were taken from the Edo people of Benin in 1897 when the British sacked Benin city, destroyed the royal palace and looted the kingdom's vast wealth - including over 2,500 works of art that can be found today in museums around the world. Addressing colonialism in the classroomPart of legacy of colonialism is that the history of art taught in schools is skewed towards Western Art, mostly made by white males. This isn't a fair picture of art history. Fortunately, curriculums like AP Art History, which I use my art history classes, now have a global focus. In my visual arts classes I make sure to give my kids access to diverse art by following my rule of 3; for every white male artist I show, I show two artists who are not. This was hard when I first started doing it, but it seems easy now because contemporary art is truly global. In this image, from an article I wrote for the Art of Education, you see an example of my rule of three. Image 1 is Caravaggio, image 2 is his near contemporary Artemisia Gentileschi and image 3 is by contemporary artist Kehinde Wiley. All three works are versions of the same subject - the biblical story of Judith and Holofernes. Studying all three points of view together adds depth and meaning. Including more than western art in the classroom is a good first step, but I've realized to truly address equity in my classroom I need to also teach about the issues that make our society unequal. So when I talk about Greek art I talk about the achievements of Greek democracy, but I also talk about the women and non-citizens who were left out. When my art history class learns about African art we learn about objects and culture, but we also talk about how many of those objects ended up in western museums. My job is not just to teach students to appreciate, but to understand and to question - that includes the legacy of colonization. We have to address it to move past it.

4 Comments

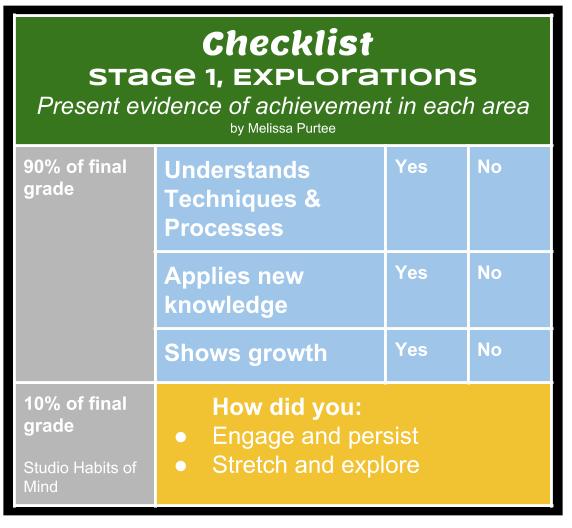

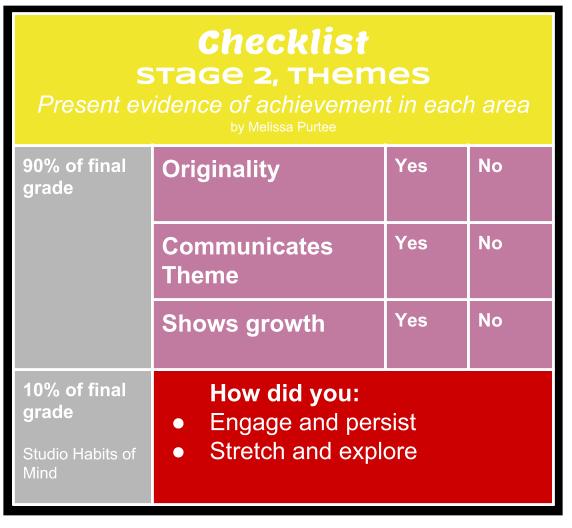

Grading is a thing I think about - a lot. I've been thinking about how to grade students' art experience in a way that is meaningful and valuable to them since I started thinking about how to make TAB work at the high school level in 2013. I've tried lots of things that mostly involved minimizing and simplifying grading. There are lots of good ways to grade, as well as to teach, but simplifying grading did not work for me. When I simplified grading, giving all students who met expectation the same grade, it did not feel like I was recognizing or reinforcing their individual learning experiences. It made the grade feel arbitrary and worked against the intrinsic motivation I was trying to foster. Many kids figured out that if they finished some art and did their blog posts, they'd be fine. I didn't want students who stopped at "fine" - I wanted more. So this school year I've been thinking about how to personalize grading. Moving Away From Blog Posts.I like the idea of blog posts; students reflecting, putting their ideas in writing and compiling a digital portfolio. All great in theory, but less so in practice. There were two big drawbacks from blog posts that I noticed: - It was challenging for me to give kids the timely feedback they needed to clearly express their thoughts. - Due reading articles like this and this - about the negative impact technology has on children, I've been realizing that I want to be more intentional about how students use technology and increase face to face interaction. I plan to still have students create a digital portfolio, but they will spend a few weeks working on it at the end of the course, not posting weekly. In lieu of weekly blog posts, I've been grading through face-to-face conferences with students. Grading through conferences has helped me get know students on a deeper level and understand their work/ work process better. It's also given me an opportunity teach the thinking I often noticed was missing in student writing; how to use evidence to support claims about what they've learned. Three Stages of LearningThis year, I've separated my beginning class into three stages: Explorations, Themes and Portfolio. The focus of each stage is different, with end goal of all students able to use their studio to make the art they independently envision. I grade the work in each stage by conferencing with students, who are responsible for presenting evidence of meeting learning goals. The evidence they select includes finished artwork and development materials like sketches, research and experimentation. After we review the evidence if they haven't meet specific goals (and therefore have a lower grade), we problem solve, together, what they can do to meet them. Students can provide evidence for a higher grade at any time during the course, with no penalty. I talk with students about their work and process daily in informal conversation that happen during work time. Grading conferences are more formal and private. I sit at my desk and the student brings their work and evidence over. It's a bit removed from where the class is working and much easier to have a few uninterrupted minutes. What students learn and have to provide evidence of in each stage: Stage 1, Explorations. Students learn about a range of media and process through a combination of experimentation and self-directed work. Media is sleselected by me or is limited to a few options (example - acrylic or watercolor paint in the painting exploration) ATP is introduced and directly taught. Stage 2, Themes Students experience generating ideas, selecting media/ processes and developing concepts from thought to finished product through working with themes selected by me. Stage 3, Portfolio Students apply everything they've learned in this stage. They independently select a theme or learning goal for the focus of a collection of work. This work is posted to a digital portfolio, created with weebly, along with work that shows evidence of what they've learned during the class, with a focus of showing evidence of growth. So far, I'm noticing that the grades students and I arrive at through conferences feel both meaningful and personal. I find that the quality of evidence that supports students' claims about what they've learned is vastly improved by my ability to ask clarifying questions on the spot. When they are unable to provide evidence they understand where they fell short and know what to do to fix it.

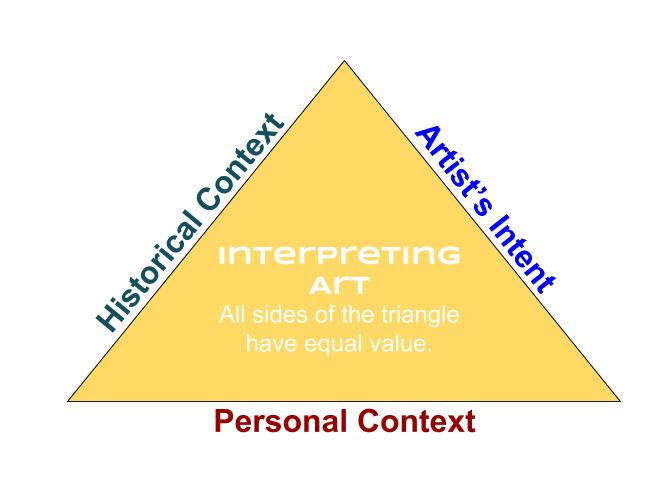

Having this conversation face to face has been delightful for me. It's helped me understand where my students are in their learning and made it easy to provide individualised support. I'm also beginning to notice a shift in work ethic since I've started tying 10% of each grade to the Studio Habits of Engage & Persist and Stretch & Explore. Students have to persuade me that they've earned some or all of these extra points, which has resulted in lots of reflection of past and current studio practice. Overheard last week: Student 1 - That drawing looks good. Student 2- The face shapes not right. I'm redoing it. (Yelling) MS PURTEE I'M PERSISTING! I used to think look in at an image was like trying to figure out a puzzle - If I was smart enough I could figure out the meaning. I brought this understanding to my teaching in the form on lessons based on specific artists and the formal qualities of art. I'd show Van Gogh and talk about line and texture and color, then have my kids "study" the work by making child friendly replicas. I use the term "study" in quotation marks because I now realize that there was little studying going on and a lot of listing to me and following my directions. Later, though my approach to art-making became much more student directed, I brought a similar approach as before to looking at art with my high school students, especially in my art history classes. I'd make bulleted lists on my slide show presentations of all the important information they needed to know, then I'd tell them about it. My approach now is so, so different and much more impactful. Instead of starting with me, I start with them. What do you see? I ask, then wait. They do the rest. I learned this visual thinking strategy, as well as many more as part of the Fellowship for Collaborative Teaching I'm participating in this school year with the North Carolina Museum of Art. In the image above, of the Aztec Sun Stone, my students, just by looking at the image with no context from me, were able to pick out almost all the important aspects of the work I'd address myself. Some were comments were in the form of prior knowledge - "I've seen this in Mexico City! It's bigger than the wall!". Some were in the form of observation based in the work - "The sun looks like a skull". Some were questions - "Why does the skull have hands?" All these contributions to the discussion work together to make collective meaning much deeper than I could make on my own. When I did discuss my knowledge of the work the students were curious and engaged, waiting to find out what the artist's intent and the cultural significance of the work were.  What I've realized this school year, through putting what I've learned during the NCMA Fellowship into practice, is that personal context is a powerful lense to approach images from. It's inclusive, engaging and welcoming. Art is not a puzzle to figure out and teaching it can't be just about what I know it means. Looking at art with students is a journey that works best when I start with them. For great resources check out NCMAlearn and Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS)

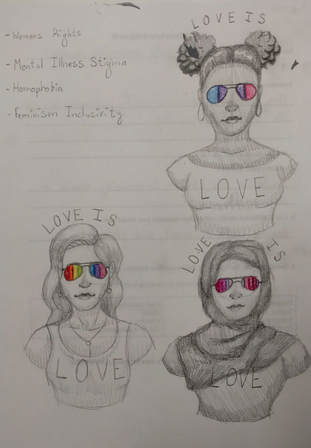

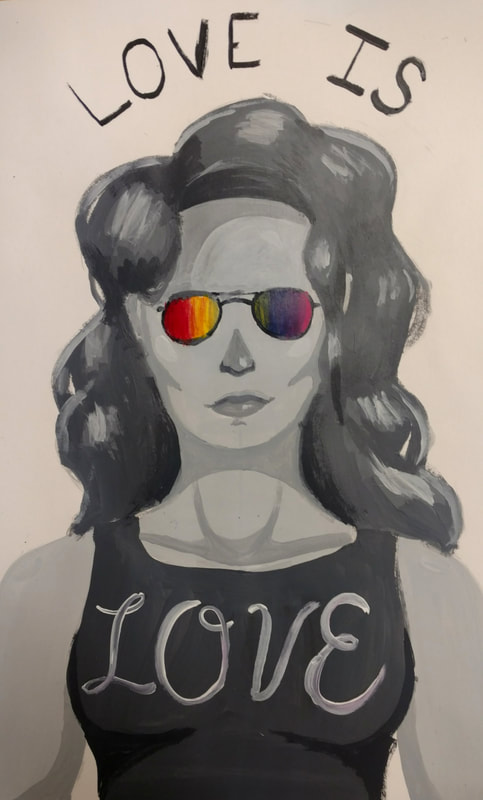

Thanks to Kristin, Jill and Michelle for all you do for teachers.  "Persuade Me" development stage personification of mental illness. "Persuade Me" development stage personification of mental illness. This year I'm trying something new with my high school beginning visual art class. I've broken the instructional time down to three main phases.

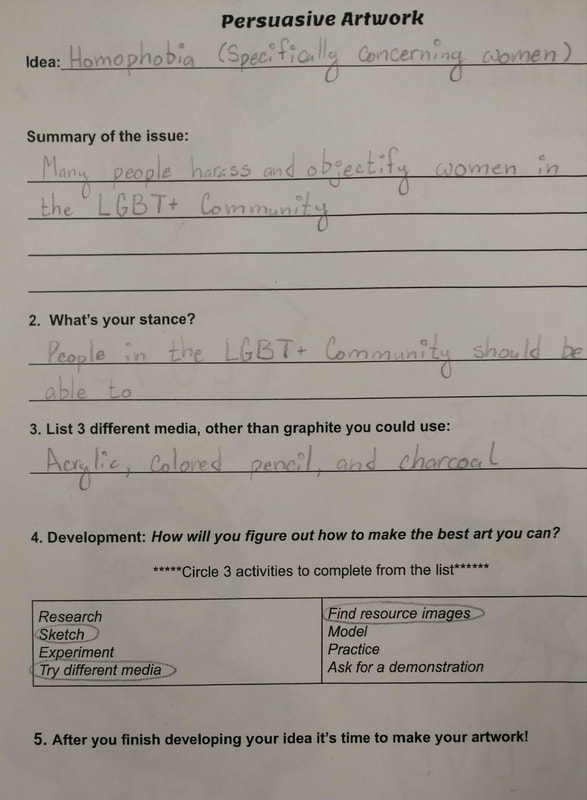

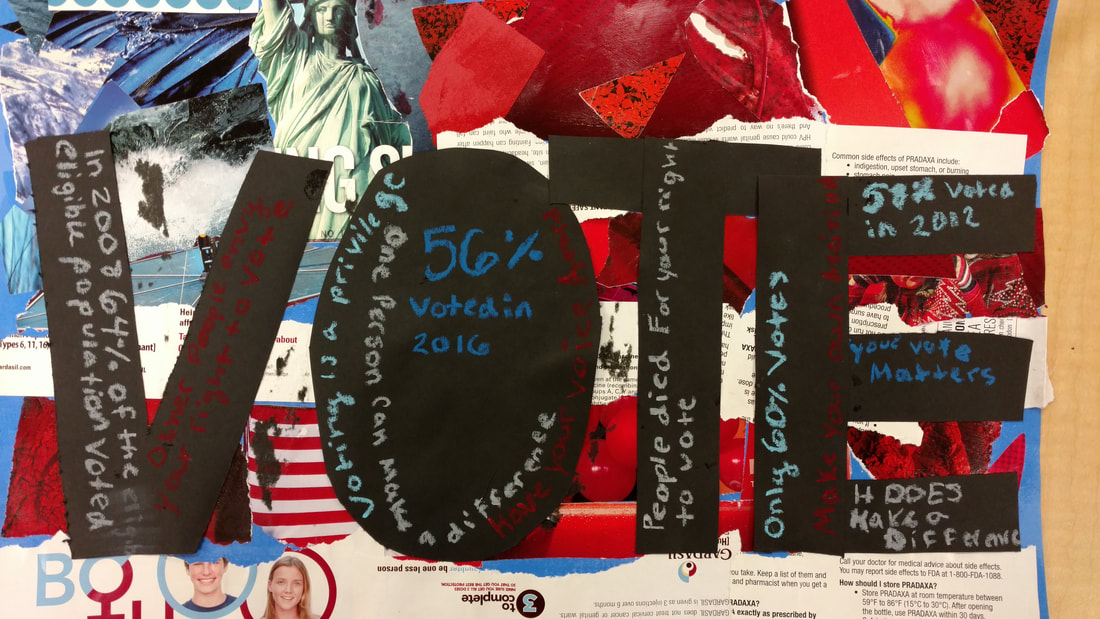

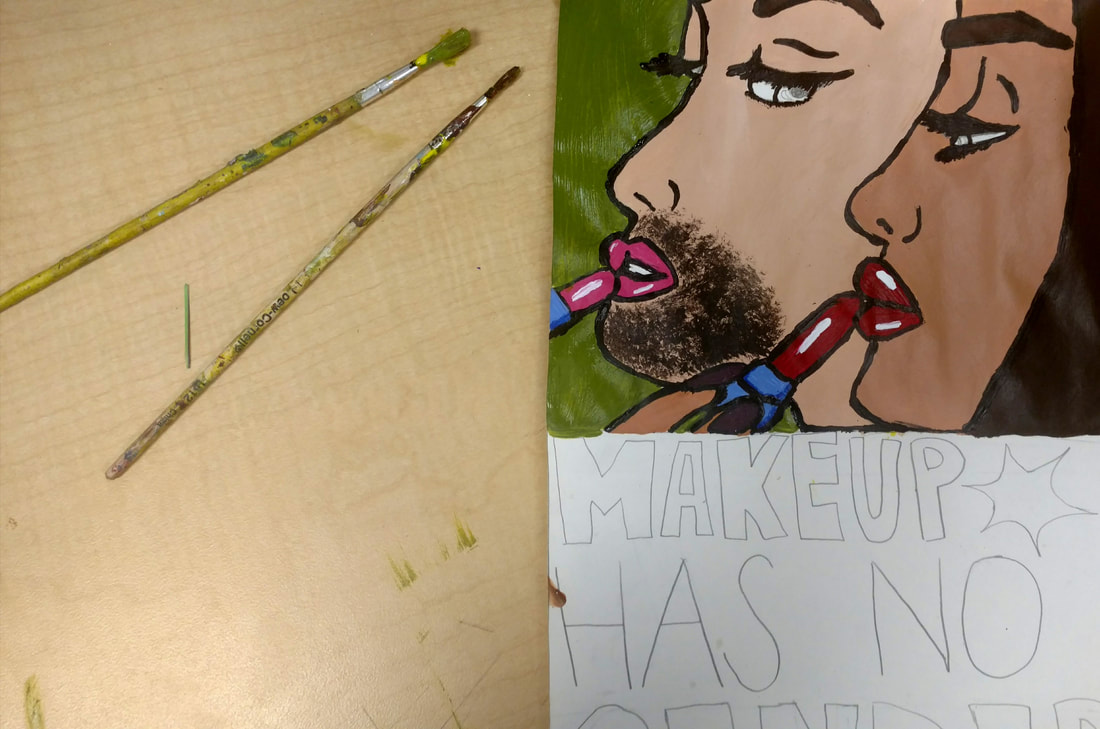

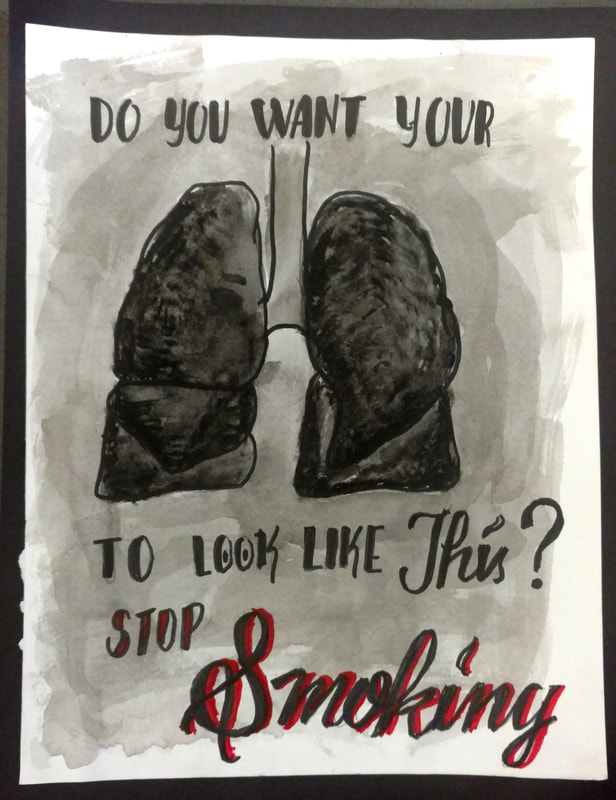

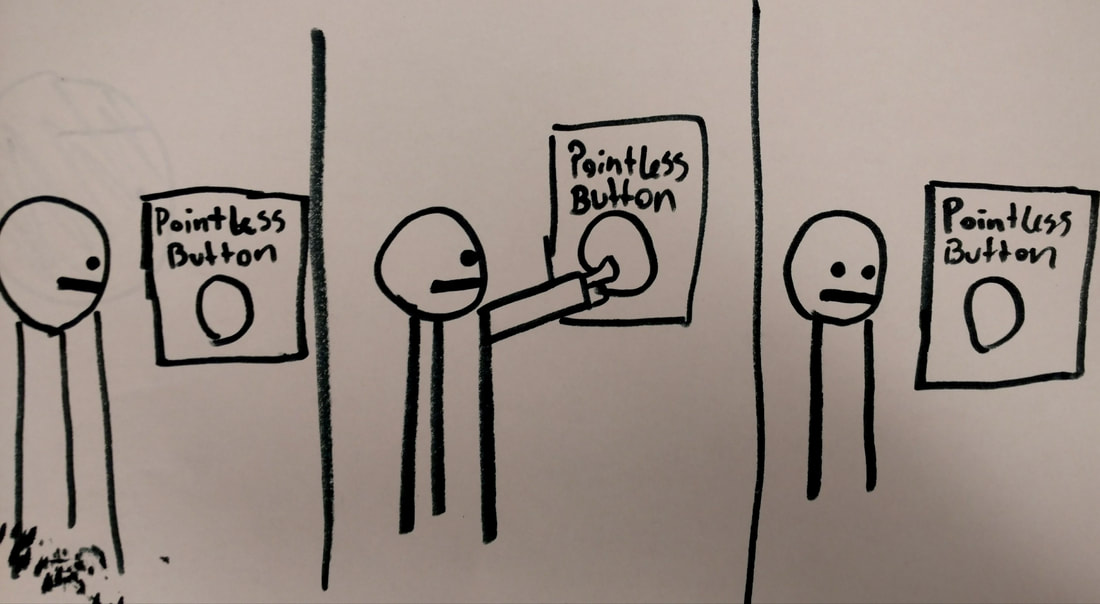

I consider this structure TAB, or Teaching for Artistic Behavior, because it is very intentionally designed to support the student as an artist, and ends with all students knowing how to have an idea and use the resources of the studio to pursue it. Two weeks ago we started the first theme of phase two. I was excited to introduce the theme, "The Things we Fear", but noticed two issues - students were skipping steps of the Artistic Thinking Process and everyone was using graphite. For our next theme I knew I needed to better support students as they navigated the art-making process I'd taught them in the Exploration phase. I modified a form I'd used before and printed one for every student, passing them out during the introduction of the theme "Persuade Me". For this theme I asked students to pick something that they had and opinion about and visually persuade the viewer to their point of view. It's a big theme and the success of the work hinges on a clear understanding of the issue student chooses to focus on. The form I created was very effective with helping students develop their ideas and decide on what to say. I decided to add one limitation to the experience - no graphite drawing for the final work. Over 90% of students selected graphite as the media for their first thematic work and I wanted to force them to branch out. Including this limitation at this moment was right for my kids because it caused them to examine different media instead of picking what felt the most familiar. See one students' process below. And more work, some still in progress. It's been a good week!

Students spent part of one class investigating how to create photos inspired by the theme of "Things We Fear". This exercise was a short, group project intended to serve as a inspiration/ development stage activity to help students work through ideas for self-directed work with the theme. We started this mini lesson by looking at Hoffine's work to identify important element of images that include an element of fear: the unknown, dramatic angles and heightened contrast were all on our list. I asked groups to create an image to share in 30 minutes, and required that they used a prop and edited the images. Some groups easily created effective images with no help from me. Other groups needed more support. The most effective part of this experience for students came when I conferenced with groups that had images that needed editing. I was able to ask them questions that helped guide them to better communicating the theme. "Do you need so much of the wall above the figure?" "I notice you're smiling in the image - does that communicate what you'd like it to?" "I wonder how adding more contrast would impact the mood?" I loved how students were easily able to edit photos and see how much these changes impacted the image. Composition is something that students often struggle with and this activity made the impact of compositional changes very tangible in a way that sketching ideas for a drawing or painting can't. Next year, instead of a mini lesson, this will be a multi day experience, with groups having a few days to create props and stage scenes to create a series of images that tell a story. I think it will be a perfect bridge between learning about media and processed in Explorations and the more open ended, self- directed work I'm asking for in addressing themes.

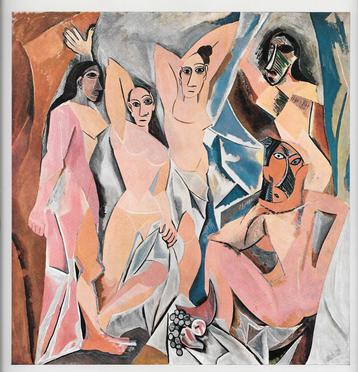

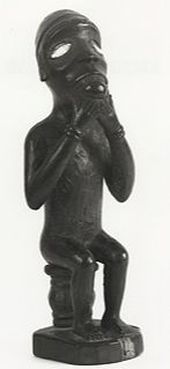

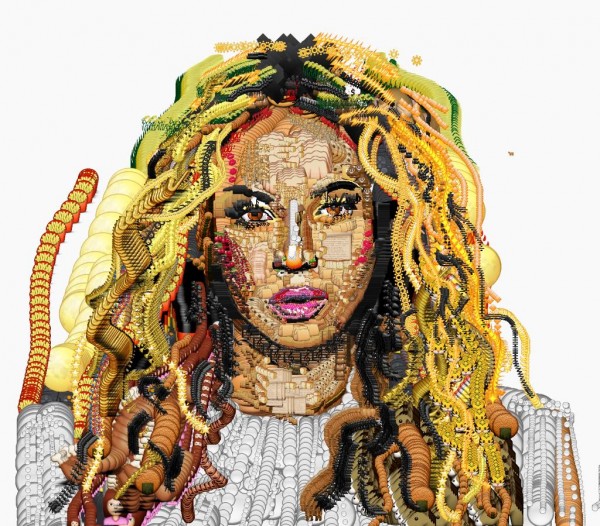

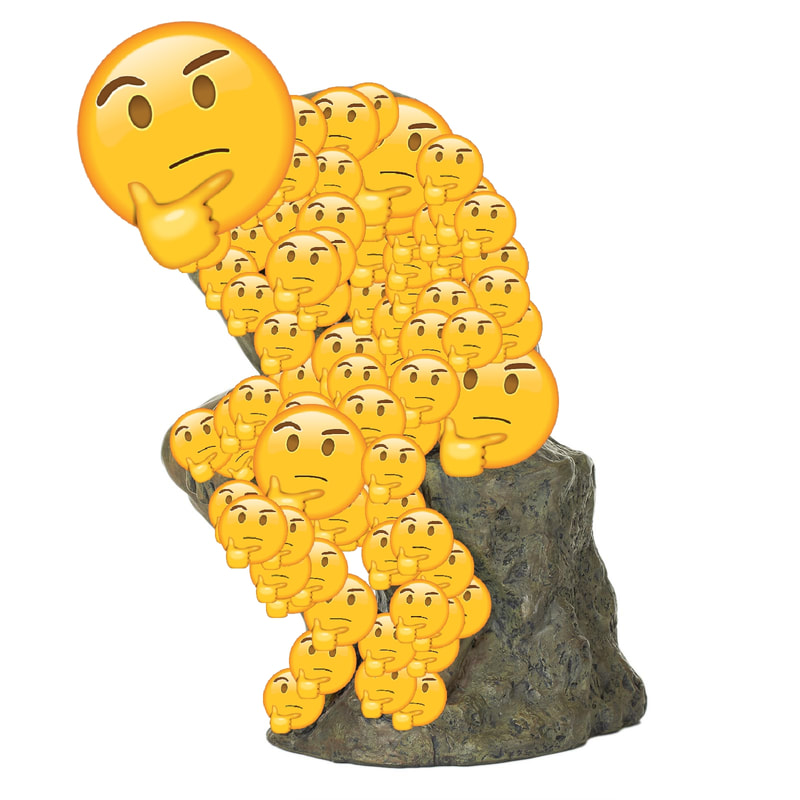

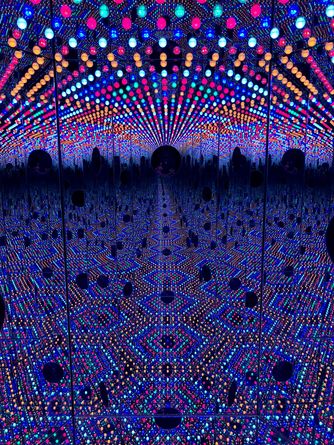

If you ask high school students what they think the requirements for original artwork are, chances are that you'll get some version of the artist-as-genius argument. Original art, this line of thinking follows, is totally unique and has never been seen before. When I have this conversation with my Art 1 students, I say sure, like Picasso. Yes, they agree, because he's one of the artists most of them have heard of. I go on to talk about how he played a central role in developing a new way of depicting images - cubism - and revolutionized the western art word. Totally innovative - except for the fact that breaking objects into geometric shapes wasn't new - artists from around the world had been doing it since forever. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, by Picasso, and a statue from the Vili people pf central Africa, which was owned by Matisse. This work had a huge impact on 24 year old Picasso. Read here for more in depth information. Picasso genius wasn't in creating something totally new, it was in combining inspiration drawn from other artistic traditions with his own knowledge. This idea of originality, as something approachable that we can all do, is what my students need. We try this out in a short group exercise. I share a list of some ways to remix the familiar, including juxtaposition, changing a fundamental element, the addition of text and using unexpected media, then show some Dorina Lynde and some Yung Jake. Next, I share a list of iconic artworks, and challenge groups to use digital media to reimagine one. They have around 30 minutes to create before presenting what they make to the class. They run with it (see student work below) using some apps I've heard of, but others I haven't. I've taught this lesson before, but this is the first time I've required digital media. It makes for a much better experience, because it requires students to consider the art-making potential of technology they use everyday, plus the ease in which these images can be created is very conducive to the sort of play that gives the images below life.

I love this art-making experience because it challenges kids to think about what originality really means, as well as to examine the creative potential of digital tools as they create with images that are culturally relevant to them as individuals. It creates the perfect reference point for the first time someone wants to copy an image from Pinterest or draw copyrighted material. Plus, it's fun.

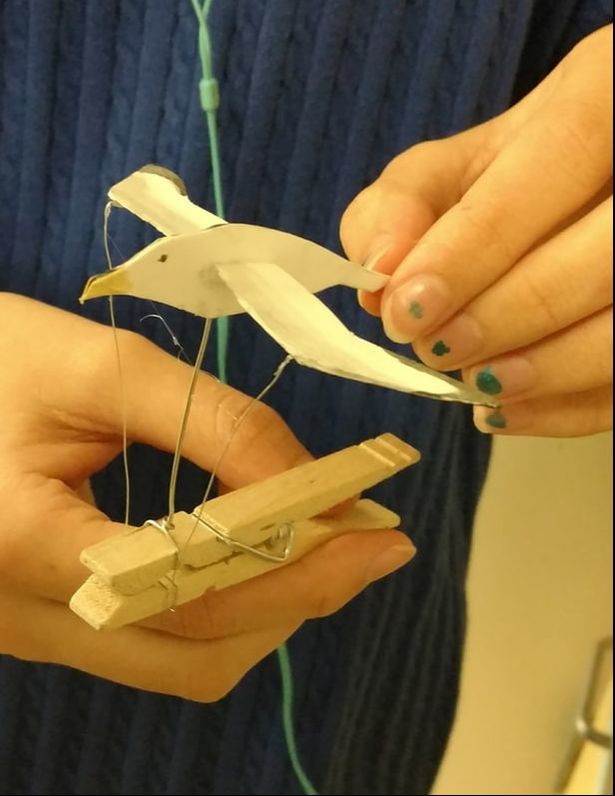

Like many art teachers, I feel like I should teach a set of skills that haven't changed much since the Renaissance and I start with those. My thinking has been to "build a foundation to support choice". That foundation, I've slowly realized, doesn't support what I think it does. Instead, it reinforces outdated notions about what makes art worthwhile. Also, the skills I feel pressured to focus on show a western art centered bias - one I'd like to think I don't have. El Anatsui, Lines that Link Humanity - literally made out of discarded bottle caps. This is art, I say on the first day. We play an awesome, creative, stimulating game. My class seems fun, they think - then they come in the second day and start with drawing or painting Bootcamp. These are well designed experiences, and most kids enjoy them, but they reinforce an understanding that's probably been building since they first walked into an art room (unless they got lucky and had a TAB teacher) - that realistic art is good and their value as an artist is directly related to their ability to render. This message is the exact opposite from what they need to hear. What I need to show them, with what I teach as well as my actions and words, is that everyone can make successful art, that good art is as varied as the individual humans that make it and that they - each and every one - have something important to say. Just getting started: working with wind, collage and exploring clay technique. So, this year we aren't drawing until well into October. The class started with kinetic sculptures. then moved to collage and now clay. As a high school level beginning art teacher, I have to start with a media overview, and and these are all open-ended explorations that have multiple avenues to success. I'll teach a variety of drawing and painting processes this year in a similar format, but I'll do it later, when my kids have started to all see themselves as successful artists. As for any skill I feel like I "need" to teach, I'll reflect on these words, shared with me by Stacy: "If someone says to you, “You have to know the rules before you can break them.” Ask yourself, whose rule is that? And, how has that rule served to silence those who don’t fit the dominant paradigm?…Standards were developed by people. By sincere people reflecting their best understanding of the arts and culture at that time. Times change. It is our job as contemporary artist educators to teach the most useful, complex, artistically sophisticated version of art education that we can now imagine." - Olivia Gude, Meaningful Making: Why We Need New School Art Styles Here's to a year of amplifying student voices and making rules that best fit their needs.  There is a pervasive preference in art education for realism. This school year I'm taking steps to end it in my classroom. I only recently realized how the choices we make as a teachers communicate to students that representational work is better. I noticed, again and again, kids in my classes with the attitude that the less close work is to realistic the less talent it takes - even students who excel at stylistic expression. Where, I wondered, does this mindset come from? It starts with the skills we teach. Students need a foundation to support more independent work, we think, so we show them how to capture what they see. Proportion, perspective, value, shading, mixing the correct colors - all of these important things require time and attention. It’s important to learn the rules before we break them, we think. Once they know enough, maybe then we can ask our students what they want to make, but by then it’s too late for many, who’ve given up because their value gradation was lacking or because they just got bored. What if, instead (or at least along with) we taught other skills, skills like independent thinking and questioning? Instead of showing students “the right way” what if we asked them what the possibilities are? Sure, we could include some traditional technical skills but they need to be in their proper place for the contemporary art world. Not in front, but instead to the side, driven by how they can support the artists' intent and meaning. If we taught this way our students would start to see talent not just as who can paint the most realistic apple, they'd see in in something innate in all of us. Of course, we teachers have to believe that first.

On the first day I always provide an overview of the class, but I don't do it by reading from a syllabus - I do it by setting up an interactive team challenge that introduces students to my Artistic Thinking Process.

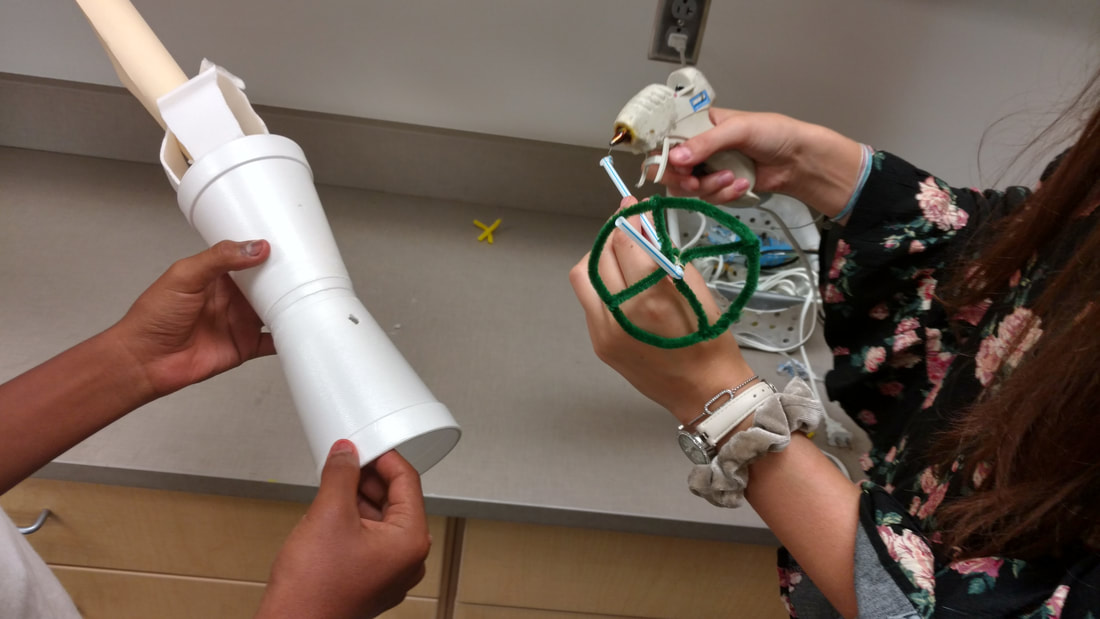

This year's learning challenge was modified from this lesson from the North Carolina Museum of Art's NCMALearn, which is full of amazing resources that I learned about this summer as part of the museum's Fellowship for Collaborative Teaching. Inspiration & Development

I started the activity by challenging groups to make a kinetic sculptures. I asked them to develop an idea by observing Vollis Simpson's Wind Machine through the video below. Students looked carefully, writing down observations about how they observed the sculpture moving.

Next, I asked groups to dig a bit deeper by researching kinetic artwork on This is Colossal. Groups used the search function to find related artwork, then presented a work that inspired them to the class. Theo Jensen's work was a favorite. Creation

I passed out bins of materials from the dollar store that contained cups, styrofoam trays, brads, pipe cleaners, popsicle sticks, cardboard and long strips of paper.

As students worked to have work ready to present in 45 minutes, I observed them at work and prompted groups to test their ideas at the wind station, were a blow dryer was set up, and to reflect on what they noticed. Kids worked, tested, revised and refined!

Students spent the last few minutes of class presenting their work by demonstrating how it moved in front of the class. The goals were:

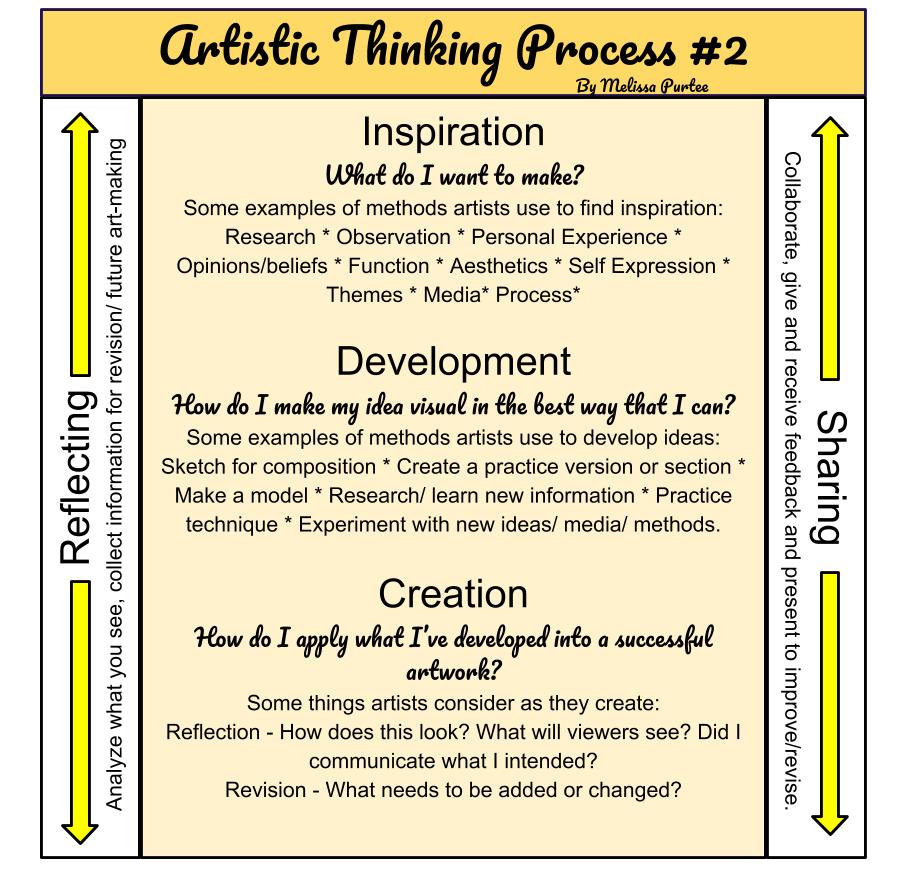

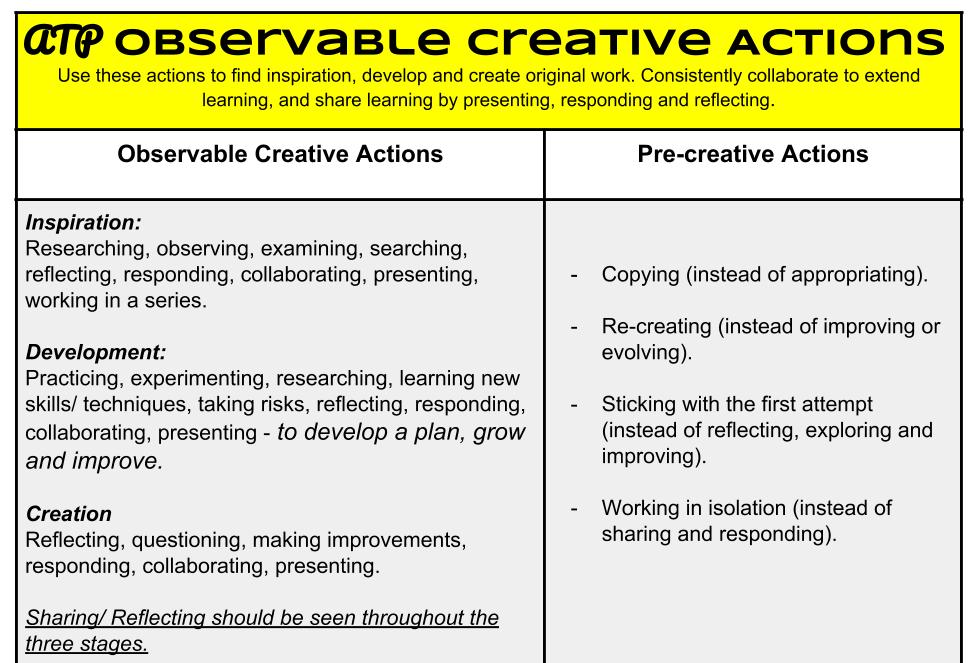

Some student work: The ability to create is innate in us all, but many students unlearn it as they go about learning how to be "good students" in school. Often, schooling teaches kids more about how to pick the right answer than to ask the right questions. In order to teach student how to think creatively, we have to show them what the process looks like, step by step. To make it flexible enough to apply to diverse ideas, we have to teach a range of customizable options and the skill to select the ones that work best. This is what that process looks like in my high school art room. Acquiring a new set of skills takes time and effort from both teacher and learner. To give our kids the information they need to improve and grow as they navigate an unfamiliar way of thinking, we have to provide clear feedback. I've been giving some thought to what that might look like in my classroom this year, for my students. My plan is to give students feedback on something I'm calling observable creative actions. These are actions taken from my Artistic Thinking Process that demonstrate the creative thinking I'm looking for and that I can observe in class through what I can see or student's verbal description in response to questions. In my experience, where some students struggle with creative actions is that they are not sure exactly what they look like. Often, they confuse activities that are pre-creative with actual creativity. For example, copying an image instead of combining elements to create a more original one. It makes sense that children would go to activities like copying and re-creating the familiar when challenged with open-ended tasks; that is what our school system often asks them to do. Even in art class students are often asked to re-create a teacher's model.

My hope is that sharing observable creative actions and pre-creative actions with my students will help increase understanding. I'll also use these to evaluate where student are in developing the ability to think creatively and, by comparing the actions I observe to the actions that are the end goal, give clear and specific feedback. Creativity is a learned skill that is accessible to everyone. We just have to teach it the right way. |

Mrs. PurteeI'm interested in creating a student student centered space for my high school students through choice and abundant opportunity for self expression. I'm also a writer for SchoolArts co-author of The Open Art Room. Archives

December 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed